Light and Colour Perception or Why are Leaves Green?

This post is about how we perceive colour and how this relates to art and computer generated images. I find working digitally that I sometimes forget that there’s a real world out there, of which a digital image is only an approximate representation. It’s interesting to step back from that once in a while and learn a bit more about how light and colour are perceived by our eyes and our brains. What follows is a grossly simplified description of colour vision and a little of how that relates to colours in digital images.

Why are leaves green?

Perhaps this isn’t even the right question. Colour exists primarily in our minds - leaves are only “green” because we perceive them to be green. But I don’t want to go down a philosophical rabbit-hole, so I’ll stick to why - from a biological perspective - we perceive them this way. Our perception of the colour of an object depends on several things:

- The range of wavelengths present in the incident light.

- The wavelengths of light that the object reflects or absorbs.

- The receptor cells in our eyes that detect the reflected light.

- Our brain’s interpretation of the signals from those receptors.

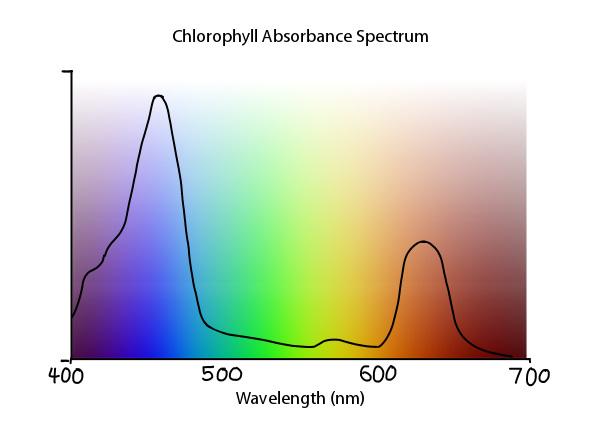

It’s important to realise that our categorising things into colours has more to do with our brains than it does with light itself. White light consists of a mix of all the visible wavelengths of light, from around 400 to 700 nanometers in wavelenth, and a given object will absorb some and reflect others, depending on what it is made of. It is a mistake then to think that a red object only reflects “red” light, it just happens to reflect wavelengths in the red region of the spectrum more strongly. The principal molecule that gives leaves their colour is called chlorophyll. Leaves are packed full of chlorophyll because it is a key component in photosynthesis, which lets plants use energy from sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide into sugars. The absorbance spectrum of chlorophyll looks something like this:

To make the best use of the incident light from the sun, which after scattering through the atmosphere is blueish in colour (observe the colour of the sky), chlorophyll absorbs as much blue light as possible - as evidenced by the main peak in the absorbance spectrum above around the indigo-blue wavelengths. The trough of low absorption we see in the middle around the yellow-green region of the spectrum gets reflected - and results in the green colour of chlorophyll.

RGB Colours

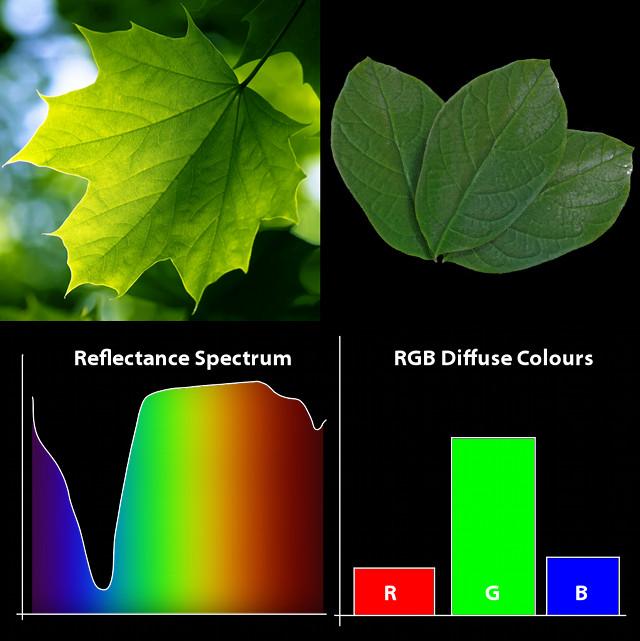

However, when we compare the the abundance of different wavelengths present in the light reflected from a leaf, with how we represent colour digitally, it initially appears like something is seriously lacking. Colour in digital images is represented by a a measly three numbers - our RGB values. How can this simple triplet of numbers compare to the far more complex spectrum of wavelengths we receive from a real object?

Colour and the Eye

The reason concerns how colour works in the eye. The cells in our retina that detect colour (called cone cells) are full of pigments that respond to light. When light hits them they change shape, and through a chain reaction with other molecules in the cell they generate an electrical impulse. But these pigments - like chlorophyll - also respond to a spectrum of wavelengths, and can’t really differentiate between them. In order to detect colour then we need three different kinds of receptor cell, each with a different photopigment with a slightly different absorbance spectrum, that responds more or less strongly to different regions of the visible spectrum of light. It’s a misconception that these correspond to “red”, “green” and “blue” light, but the net effect is that by comparing the responses from these different receptors, we can tell whether the light we see contains more reddish, greenish or blueish wavelengths. It isn’t a coincidence then that the digital RGB colour model uses three colour values, because by mixing different amounts of these three colours we can replicate the effect of (almost) a whole spectrum of wavelengths. The cells in our eyes crunch the data down into three channels in a very similar way, so we notice very little difference. (Indeed, this is in fact why the RGB colour model was designed this way).

But what about Magenta?

The next thing to talk about is how we get from the concept of wavelengths as representing colours, to the familiar idea of a colour wheel. Whilst I’ve shown already that most colours we see are made up of a whole mix of wavelengths, I’ve also been acting as each wavelength of light could in theory be assigned a specific colour. Indeed they can - as evidenced by certain kinds of light sources like lasers that can produce light of a single wavelength, which we see as coloured light, or by looking at light through a prism, split up into a rainbow of different wavelengths. However, the wavelengths of light extend off in either direction from the ends of the visible spectrum, into kinds of radiation we can’t see. So how do we end up perceiving colours like magenta which we perceive as being somewhere between red and blue?

The answer this time lies in the brain. Once the receptors in our eyes receive light, they pass this on as an electrical signal up the optic nerve to the visual cortex, at the back of the brain, in the occipital lobe. Here the three-channel model of colour is abandoned and replaced with a four-colour opponent-processing model. Neurons early in the visual cortex are clustered in regions called blobs, some of which compare the signals from the different cone cells, to decide whether light is more blue or more yellow, others whether it is more red or more green. The output from these clusters determine how we perceive colour , and the grouping of colours into opposing pairs results in our idea of complimentary colours, blue with yellow, red with green and so on. This is also why we can’t imagine such colours as blueish yellow or reddish green - because the parts of the brain that perceive these colours treat them as being each others opposites. Our eyes could easily receive light consisting mostly of blue and yellow wavelengths, but we would simple perceive it as being more or less colourless. Non-opposing colours on the other hand can mix together, giving us orange between red and green, and cyan between green and blue. This also results in magenta - a mix of blue and red light from either end of the spectrum that we perceive as a single colour, even though it has no analogue on the visible spectrum itself (this is called an extra-spectral colour).

So, why are leaves green?

Because we perceive them to be green. A burning ball of hydrogen 150 million kilometres away emits light of all kinds of wavelengths, which travels to earth, scatters through the atmosphere, and gets partially absorbed by photosynthetic chemicals. The rest of that light gets reflected, then absorbed by pigments in cells in our eyes. The signal gets simplified, then processed and compared, passed on to other parts of the brain and we finally come to the conclusion that leaves are green. Simple right?

Comments

Ben Simonds (May 31, 2013)

Possibly. It’s could also be that producing pigments to absorb the whole spectrum of visible light would simply be too costly for the plant, when the payout from just producing chlorophyll is good enough as it is.

scape (May 31, 2013)

Black = hot

reavenk (May 31, 2013)

There’s also the question of if leaves are supposed to absorb light as efficiently as possible, why didn’t they evolve to be black and absorb that green wavelength also.

Rowilson (Jun 05, 2013)

El cerebro se invento el magenta y ahora es; Red: 1.000, Green: 0.0, Blue: 1.000.

Google Translate version:

“The brain was invented and is now Magenta, Red: 1.000, Green: 0.0, Blue: 1000.”

scarodj (Jun 22, 2013)

Interesting. You have a nice way of explaining it. Thank you.

^ Wow, Google didn’t translate that properly. He said: “So the brain invented magenta and now it is R1.0 G0.0 B1.0.” <- Blender input, hehe.

Need To Know The Color of Sky in RGB Format? | Grayson Peddie (Oct 01, 2013)

[…] Light and Color Perception or Why Are Leaves Green […]

bashi (Oct 14, 2013)

Great Post, have to read more often here.

スーパーコピーバッグ (Sep 30, 2018)

2018年人気貴族ブランドコピー(N級品)優良店!

ルイヴィトン、シャネル、グッチ、ロレックス、バレンシアガ、

エルメス)、コーチ、ブラダ、クロエ大激売中

★高級品☆┃時計┃バッグ┃財 布┃その他┃

◆★ 誠実★信用★顧客は至上

●在庫情報随時更新!

品質がよい 価格が低い 実物写真 品質を重視

100%品質保証 100%満足保障 信用第一

★人気最新品┃特恵中┃☆腕時計、バッグ、財布、ベルト、アクセサリー、小物☆

★当店商品送料無料日本全国!

休業日: 365天受付年中無休

Easwar Kumar vb (@easwarkumarvb) (Aug 07, 2015)

Neat article …nicely explained.

bob (Apr 19, 2016)

your face

bob (Apr 19, 2016)

no

vigneraj (Nov 24, 2015)

nice

Franchesca (Oct 05, 2016)

If you are interested in topic: earn online by watching ads for cash - you should read about Bucksflooder first

azim (Oct 03, 2014)

i think leaves are not a green colour.because leaves are made up by all colours. this cause leaves are reflacted the green colour.

Gordon (Apr 02, 2015)

No, they are not even reflecting “green colour”. Did you actually read the article? g

Sex (Nov 26, 2017)

Why not talk about babies

(Feb 28, 2019)

ºþ±±Ë¼ÇÚÖÇÄÜ×°±¸ÓÐÏÞ¹«Ë¾»ùÓÚ´óÊý¾ÝºÍÈ˹¤ÖÇÄܵÄģʽÔËÓª·½Ê½¡£

john (Oct 03, 2021)

I’m think light and sound is just a frequency and perceived by animal and humans.

brain, colour, eyes, green, leaves, light, perception, resources — May 30, 2013